Exclusive Interview: The Creators Of The “Shared-Footage” Horror Film MAN FINDS TAPE

"We just wanted to get weirder and bigger."

"We just wanted to get weirder and bigger."

Peter Hall: Yeah, one of the things that interested us about making a fictional documentary, particularly in this time period, is that we have long since entered a world in which footage is readily accessible anywhere—all the weirdest stuff. There are lots of internet rabbit holes to fall down, so we particularly wanted to tell a story about someone exploring a piece of viral footage.

You know, if The Blair Witch Project had come out now, and nothing had existed in this genre before, those filmmakers would have uploaded that footage to YouTube. And then there would be people commenting, “Oh, this is fake as shit,” and other people would be like, “No, it’s totally real.” We wanted to acknowledge the time we’re in, and the way in which viral videos factor into a part of our lives that’s sort of unavoidable.

Paul Gandersman: I also feel like there was a long time when you would see video footage, and you would have to be given evidence to prove it was fake. Now, if I see anything that looks wild, my default is that I need it to be proven that this is real. We’ve kind of inverted, at least for me, how we view the world. And that was an interesting idea to play around with.

You start the movie with the Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot film, and the famous Loch Ness Monster photo. Did you grow up being into this kind of cryptozoology?

PH: I was a huge cryptid fan growing up. I was obsessed with all of it, and wanted every single cryptid to be real. I went on lots of camping trips and things like that as a kid—I was in the Boy Scouts and whatnot—and I was always hoping there was some weird thing lurking out in the woods.

PG: I grew up watching The X Files with my dad, and he took me to see Blair Witch in the theater in ’99. I was old enough to know those things weren’t real, but I was always fascinated by the concepts and how entertaining it was, at the time, to go down these rabbit holes. Going down a conspiracy theory rabbit hole is inherently fun because you’re peeling back layers of the story. It’s the same reason we enjoy movies like this, right?

Often, movies like Man Finds Tape involve a lot of improvisation. Was that the case here, or was it pretty tightly scripted?

PH: It was a little bit of both. The film was heavily scripted, and that was very meticulous because we spelled out what angles the shots were coming from, what type of camera we were looking at, because we used lots of actual mini-DV cameras, we had security cameras, and we had the modern documentarians’ cameras, which were Sony FX3s and 6s. We had like 100 different types of cameras on this movie, so we were very scrupulous in that regard.

During the actual filming, one of the things we talked about with all our actors was giving them permission to find new dialogue or new moments in the scenes. As long as it all stayed within the structure we were building, and knowing that we had to hit certain beats and intentions for the plot and the themes to work.

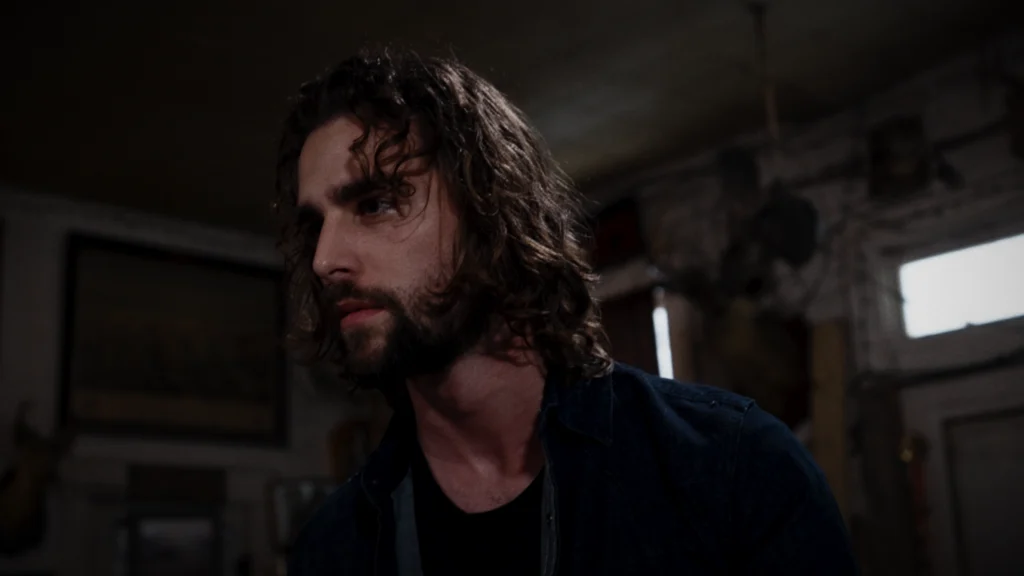

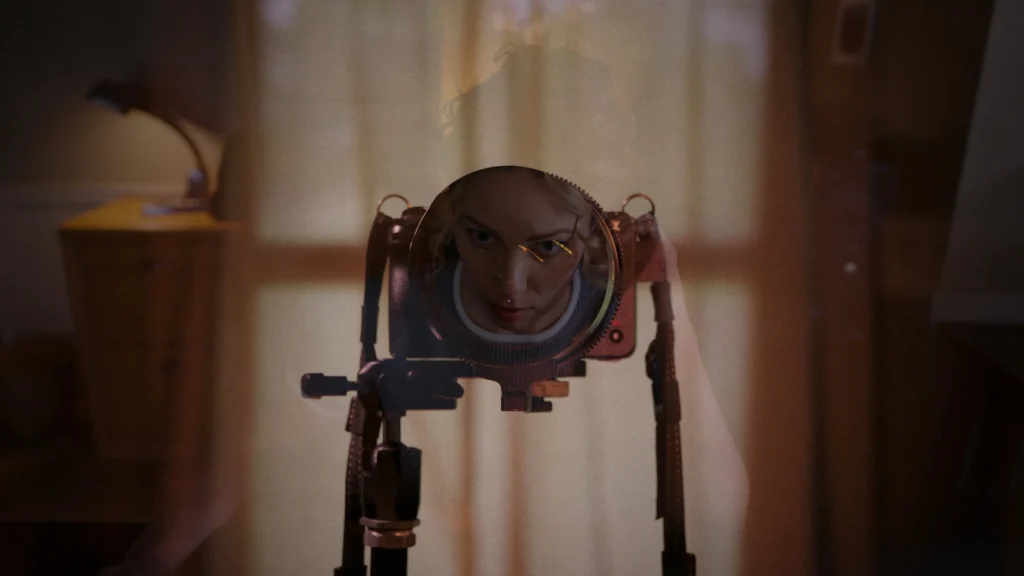

PG: Also, a lot of what we were asking these actors to do, especially Kelsey Pribilski and William Magnuson, involved holding the cameras themselves. It was kind of double duty: creating the look of the movie, and also their performances. We looked for actors who were willing to challenge us in a way that forced us to think about those elements, so what the camera was doing felt motivated by character.

There were times with Kelsey in the barbecue scene when we were blocking it out with her, and she looked at us like, “There’s no way I would go there in this moment.” And we said, “Shoot, yeah, you’re right. What would you do?” Then we worked it out with her in character and adjusted how we were shooting it based on that. It was really a partnership where we were looking to them to bring stuff.

PH: I believe that when people think of improv in films, they just think of dialogue that the actors come up with on the spot. Improv for us often fell back more toward the production side of things, where we would reblock or restage a scene in the moment because when something horrible was happening on camera in front of an actor, they may not have approached it quite as quickly as we had scripted, or they had a different reaction to this shocking thing happening to them. We worked with them to figure out the right balance between what we needed to happen and how they felt the characters would approach what was happening.

Man Finds Tape deals very heavily with religion. Is any of that inspired by your backgrounds?

PG: Not necessarily the Texas element; Peter and I are both Texas transplants. I definitely grew up among religion and Catholicism, with Judaism mixed in—I had a parent in one of each. But when we were writing the story and the characters, it felt like a natural element that made sense in a small Texas town, with a character who naturally had power in that community.

I believe John Gholson, who plays Reverend Carr, brought a lot of his past to it, because he did grow up in Texas in an evangelical community. The opening of the film is about a 90-second single take of him speaking to camera, and he improvised that. He just said, “Hey, guys, I’ve got an idea. Can I try something?” That’s how researched he was, that he was able to come up with that on the fly.

PH: I had a similar sort of background to Paul, where I myself was never wildly religious, but I grew up attending church services through my grandparents and my mom, who died when I was young. But when she was alive, she would go to church regularly, so I would go with her. I grew up tangentially to it and had a healthy skepticism of it after a while. That fed into the movie.

But as Paul was saying, we came at it less from trying to make a film that was explicitly about religion, and more looking at, who in this small town would fit this story? The idea of the reverend came from there, and then we tried to make it as thematically relevant as possible.

Can you speak about the difficulties of doing visual effects on a found-footage movie, where you don’t often have a clean or stable image to work with?

PG: It’s an interesting question. Aaron [Moorhead] did all of the nitty-gritty of that, so I can’t really speak to it, but I will say that part of what’s tricky about it is that it can’t look too perfect. Since we’re dealing with footage that is noisy and pixelated and so forth, if the imagery looks too perfect, it starts to pull you out.

Another guy, an incredible artist named Tim Buel, did something in the film, a specific sequence, and working with him on it blew our minds. Anybody reading this should look up Tim Buel on Instagram; his work is amazing. He did version one of this sequence, and then version two with upgraded equipment. And we said, “We actually need to turn some of this back closer to version one,” because it got too clean. It was too pristine and perfect, and we were like, “No, no, we need to mess it up a little bit.” It was an interesting balance.

PH: The biggest challenge in using computers for visual effects these days is that they’re coming in at such high definition, and we had to match the low definition of the footage at times. And for the most part, we had practical elements for Aaron to work off of. There are characters who have prosthetics on their bodies that go to weird places, and those were all real.

Any time Aaron was needed to augment some of those, to clean up an appliance or add a little bit of goop, he was building off of things that were already there. We used a lot of Ultra Slime on the set, so he didn’t have to create a whole lot from scratch. There’s a wormy element to our film, and he went out, got earthworms, put them in front of a greenscreen in his house, filmed them, and then comped them in. It would have been easy to just make those digital, but they are real practical elements. He had a lot of fun putting that stuff together.

PG: It really was a marriage of practical effects and visual effects that made it work. Meredith Johns headed up our special effects team on set, and 90 percent of what you see in the finished film was what we saw in person on the day.

Man Finds Tape takes that turn from a mystery/psychological emphasis to more explicit horror in the last act. Without going into specifics, can you talk about making that transition?

PG: Peter and I just like to lean into what actually bothers us, what scares us: trypophobic elements, holes in bodies, things like that. Junji Ito, the manga author/artist, was a big inspiration. Those books are very difficult for me to get through, which I think is a positive, so that was where we wanted to go with those horror elements.

PH: The first half of the film, even if it is full of dread and it’s got weird footage and such, is still relatively mundane, until that moment when it starts taking bigger swings. From that point on, we’re slowly putting our foot on the gas and hopefully taking audiences to places they don’t see coming. We could have kept the film in that initial gear and found ways to make it creepy and weird, but Paul and I are big fans of films that have that sense of escalation. We just wanted to get weirder and bigger and weirder and bigger.

PG: We watch lots and lots of horror films and indie films, and we know there’s kind of a contract with the audience: We’re asking for their time. They could be spending that time watching a $100-million movie, or they could be spending their time watching our movie, and that time has the same value.

So we wanted to deliver something that made that time feel worth it, and also pace it in a way that moves along. The movie is 84 minutes when it hits credits, and we’re very proud of that, because we wanted it to feel jam-packed and not like we were wasting anybody’s time. We wanted the mystery to just continue unraveling, and then get to a point of, “Here you go. You ate your vegetables, here is your steak dinner. Enjoy. And then here’s some ice cream.”