Effective found footage storytelling requires a delicate balance of narrative structure and chaotic realism. After all, if you make your movie too realistic, it’ll likely be about as entertaining as keeping up with a nanny cam. On the other hand, if you try to inject the story with too many of the usual tropes and […]

Effective found footage storytelling requires a delicate balance of narrative structure and chaotic realism. After all, if you make your movie too realistic, it’ll likely be about as entertaining as keeping up with a nanny cam. On the other hand, if you try to inject the story with too many of the usual tropes and contrivances that make traditional movies exciting, you’ll end up defeating the purpose of trying to emulate amateur footage in the first place. This tension lies at the heart of every single film featuring an in-world camera, and while there’s no definitive right way of doing it, we’ve seen several good films on both ends of the spectrum.

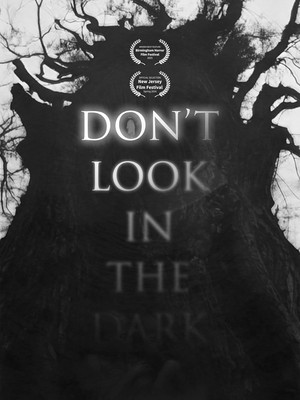

That’s why I was curious about Sam Freeman’s experimental debut feature Don’t Look in the Dark, as the marketing behind this micro-budget horror picture promised to deliver a new kind of genre experience even more understated than the original Blair Witch Project. You see, unlike most found footage movies where the recordings are intentional, Don’t Look in the Dark presents us with footage from ordinary cellphones that began recording on their own during a camping trip in New Jersey – complete with black screens and extended moments of eerie ambient sound.

In the finished film, which was envisioned as a scare-driven Rorschach test where no two viewings are the same, we accompany a loving couple on an ill-fated trek through New Jersey’s Pinelands National Reserve (also known as the infamous Pine Barrens). When Maya (Rebi Paganini) sees a mysterious child in the woods, she and Golan (Dennis Puglisi) end up caught in a possibly supernatural web of terror orchestrated by an entity that wants to be seen.

Of course, the story here is little more than an excuse to conduct Freeman’s aesthetic experiment. If you think about it, real found footage tends to be full of holes and unintelligible images/sounds. Most people don’t really focus on filming things as cinematically as possible while under duress, so it makes sense that recordings of a real horrific event would be messy and incomplete.

Unfortunately, while other found footage films have found ways to incorporate different sources of scattered evidence into a larger narrative whole (such as Savageland or even ), ultimately falls victim to its own minimalist gimmick.

![‘Don’t Look in the Dark’ Is a Victim of its Own Found Footage Gimmick [Review]](https://bloody-disgusting.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/dont-look-in-the-dark.jpg)